The pros and cons of proportional representation

Could a change of voting system heal the UK’s polarised politics?

The current parliament is "the one that least represents how the country voted of any in history", MPs have said.

The warning came as the Commons discussed how the first-past-the-post voting

system produced "the most disproportional Parliament in British history" at

the last election, said the Electoral Reform

Society.

After voters went to the polls last summer,

Labour got two thirds of the seats (63%) with only a third of the vote share

(34%). The Greens and Reform received just over 1% of seats for more than

20% of the vote share combined.

Electoral reform campaigners enjoyed

a victory in December when the Commons voted in favour of PR for the first

time ever following the first reading of a 10-minute rule bill, put forward

by Liberal Democrat MP Sarah Olney. The vote will "have no practical

impact", said The Guardian, but "symbolically",

this is "a victory for electoral reform campaigners".

Pro: better reflects voting

"Under PR systems the number of seats in parliament reflects the number of votes cast overall in elections," said The Independent. Advocates believe, therefore, that if a party receives 20% of the vote, it should have 20% of the seats.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The current first-past-the-post (FPTP) "majoritarian system", however, delivers disproportionate majorities that favour larger parties, voters in rural constituencies and does not reflect the true voting preference of the general public.

A more proportional system would also give smaller parties and independent candidates a better chance of getting into Parliament and introduce different voices to our national political life.

PR seldom results in one party holding an overall majority but rather leads to governments that need to compromise and build consensus. This means that – in theory, at least – stable, centrist policies that reflect a spectrum of views often prevail. This was the case in Germany, which had a government made up of centre-right free marketeers, the centre left and Greens until the three-way coalition collapsed last November with elections scheduled for later this month.

By contrast, FPTP "is increasing polarisation, weakening accountability, and perpetuating an increasingly dysfunctional two-party system", a report by The Constitution Society has warned.

Con: pathway for extremists

"The premise that PR can be good for fringe parties is based on a kernel of truth. In the Netherlands and elsewhere, PR helps extremist parties and radical ideas turn diffuse votes into seats in legislatures," said the Nato Association of Canada, citing a Harvard Kennedy School of Government study that found PR systems tend to favour extreme right-wing parties.

If the 2015 UK general election had been held under a PR system, UKIP would have been the third-largest party in Parliament, with 83 seats instead of one. Good news for its supporters but worrying for those who linked the party’s popularity with a resurgence of xenophobia and nationalism.

"It is undoubtedly true that PR allows for higher numbers of MPs from 'non-mainstream' parties," said Dylan Difford on the Electoral Reform Society site.

Most European parliaments contain at least one left-wing socialist and one right-wing populist party or in the recent case of Sweden and Italy right-wing populist parties can break through and win enough votes to form a government.

Pro: ends 'wasted votes'

A more representative form of PR would put an end to millions of votes being "wasted" at elections.

In 2019, for example, analysis by the Electoral Reform Society found that across the UK, more than 22 million votes (70.8%) were "ignored because they went to non-elected candidates or were surplus to what the elected candidate needed" to win the seat.

Voters "can tell when they're being ignored they can also smell unfairness a mile away", Labour MP and chair of The APPG for Fair Elections, Alex Sobel, told the Commons last week, and this means "people's votes are not equal in value".

A change to PR would mean candidates

having to appeal to a much larger section of the public rather than just

targeting a tiny proportion of swing voters in marginal constituencies. This

in turn could lead to a higher turnout at the polls, as voters feel more

engaged with the democratic process.

A study into voting patterns in New

Zealand after its switch from FPTP to PR in 1996 found that "voters who were

on the extreme left were significantly more likely to participate than

previously, leading to an overall increase in turnout". PR also fostered

"more positive attitudes about the efficacy of voting".

Con: local issues suffer

One of the main arguments against PR during the failed Alternative Vote referendum of 2011 was that it would weaken the link between constituents and their MP.

Under FPTP, MPs serve the constituency for which they campaign, so are more inclined to tackle local issues and represent the specific views of their constituents at a national level. Under the PR “list” system, electoral constituencies would have to be much bigger in order to have multiple seats to fill proportionately, possibly leading to local issues being overlooked.

Pro: more representative locally

FPTP allows MPs to be elected with a small overall percentage of the vote. Some representatives have been elected to Parliament despite 75% of their constituency voting for other candidates.

According to the Electoral Reform Society, the concentration of the Labour vote in certain areas meant that in 2019 it took on average 50,835 votes to elect a Labour MP, while only 38,264 votes were needed to return a Conservative MP.

The alternative vote (AV) system, which

is not fully proportional but is still likely to increase the representation

of small parties, and single transferable vote (STV),

which is truly proportional, would take into account voters’ back-up

choices to end up with a candidate who satisfies a majority.

Con: compromise coalitions

Talk of a so-called "coalition of chaos" made up of Labour, the Lib Dems and SNP was a feature of the Conservatives’ 2015 election campaign and fears of something similar are driving the current Labour leadership to shy away from backing PR.

In a country like the UK, which is used to long periods of single-party rule, the idea of a never-ending series of weak and indecisive coalition governments has been the main obstacle to electoral reform over the years.

Neither the trade union reforms that Margaret Thatcher pushed through nor Tony Blair’s raft of improvements to public services could have been carried through without a strong governing majority.

Detractors also claim PR carries an inherent instability. The Italian parliament, which uses such a system, is constantly in a state of uncertainty and has been prematurely dissolved three times since 2008.

Parties "diverging on multiple issues" are "unlikely to be natural bedfellows in government" wrote Nathan Wilkins for ShoutOut UK, and a "weak and divided" government "riven with factional infighting" means "very little of substance gets done". This means PR is "hardly" a "model for effective government".

There is also the messy process of

forming a coalition. In Germany in 2021, the process took three months. And

in October 2020 Belgium ended a record-breaking 653 days without a

government or prime minister when Alexander de Croo was able to form a new

four-way coalition, said Euronews.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

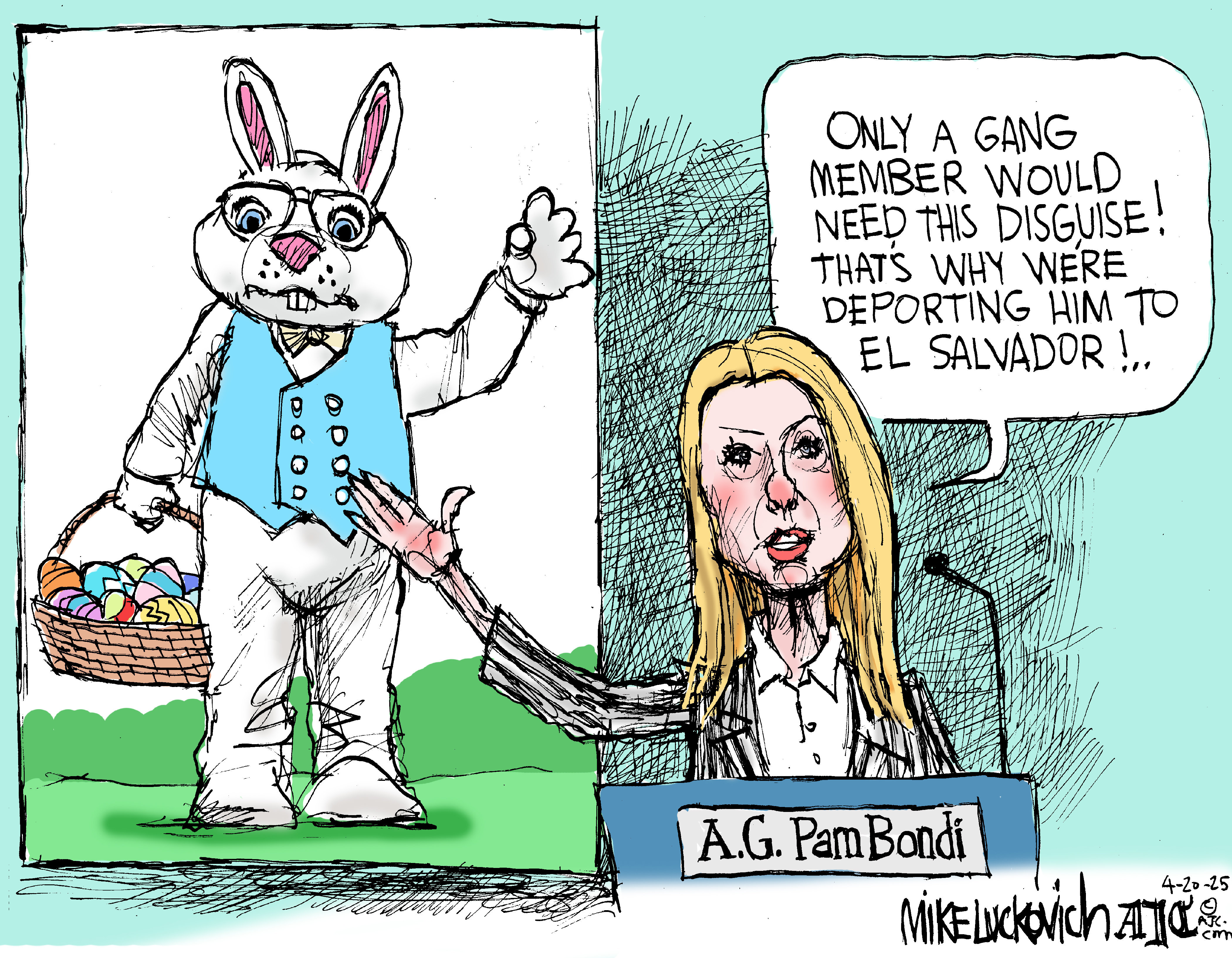

Today's political cartoons - April 20, 2025

Today's political cartoons - April 20, 2025Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - Pam Bondi, retirement planning, and more

By The Week US

-

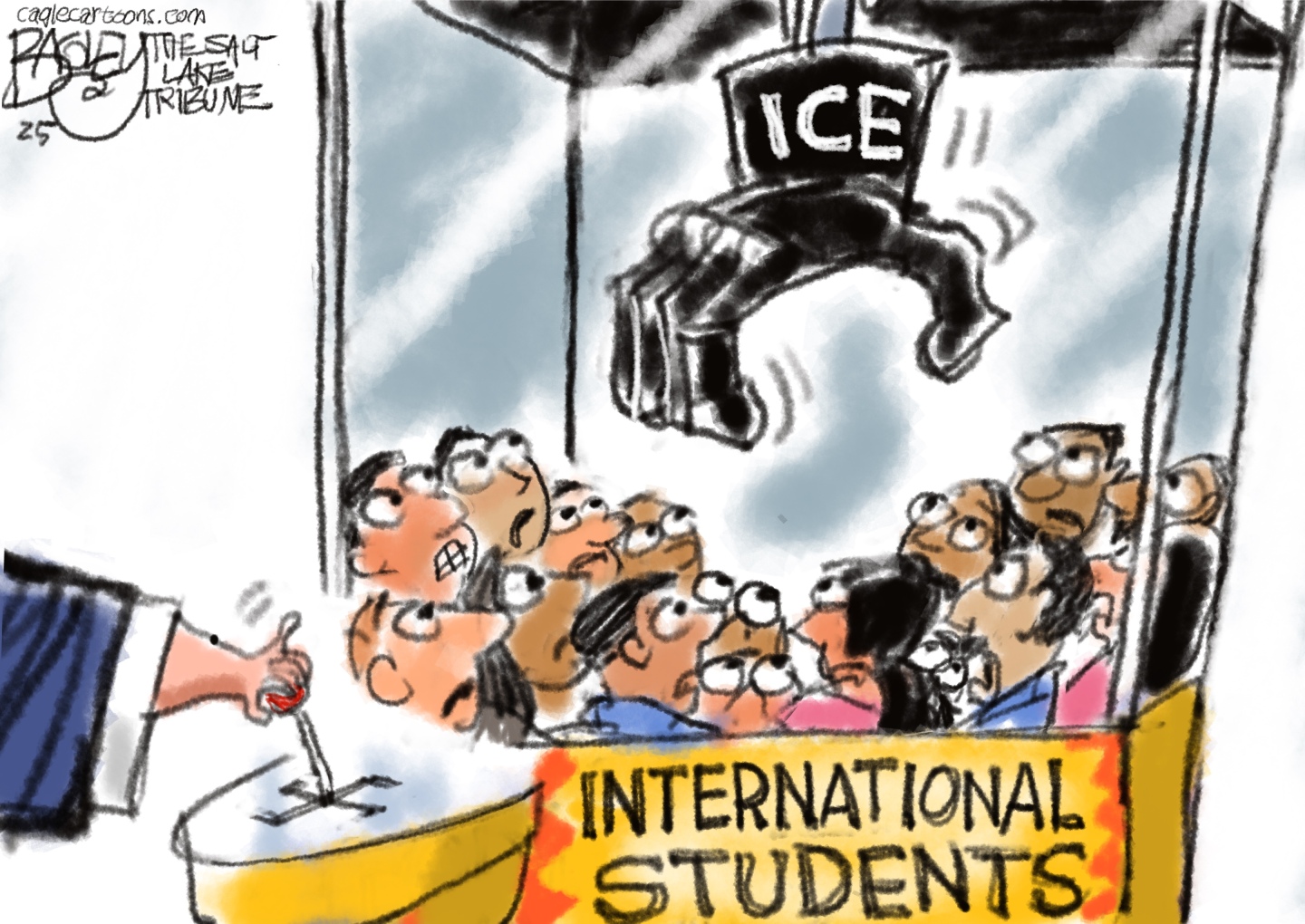

5 heavy-handed cartoons about ICE and deportation

5 heavy-handed cartoons about ICE and deportationCartoons Artists take on international students, the Supreme Court, and more

By The Week US

-

Exploring the three great gardens of Japan

Exploring the three great gardens of JapanThe Week Recommends Beautiful gardens are 'the stuff of Japanese landscape legends'

By The Week UK

-

UK-US trade deal: can Keir Starmer trust Donald Trump?

UK-US trade deal: can Keir Starmer trust Donald Trump?Today's Big Question White House insiders say an agreement is 'two weeks' away but can Britain believe it?

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

Did China sabotage British Steel?

Did China sabotage British Steel?Today's Big Question Emergency situation at Scunthorpe blast furnaces could be due to 'neglect', but caution needed, says business secretary

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

What is Starmer's £33m plan to smash 'vile' Channel migration gangs?

What is Starmer's £33m plan to smash 'vile' Channel migration gangs?Today's Big Question PM lays out plan to tackle migration gangs like international terrorism, with cooperation across countries and enhanced police powers

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

The tribes battling it out in Keir Starmer's Labour Party

The tribes battling it out in Keir Starmer's Labour PartyThe Explainer From the soft left to his unruly new MPs, Keir Starmer is already facing challenges from some sections of the Labour Party

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

Are we on the brink of a recession?

Are we on the brink of a recession?Today's Big Question Britain's shrinking economy is likely to upend Rachel Reeves' Spring Statement spending plans

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

Has Starmer put Britain back on the world stage?

Has Starmer put Britain back on the world stage?Talking Point UK takes leading role in Europe on Ukraine and Starmer praised as credible 'bridge' with the US under Trump

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK

-

CPAC: Scenes from a MAGA zoo

CPAC: Scenes from a MAGA zooFeature Standing ovations, chainsaws, and salutes

By The Week US

-

What did Starmer actually get out of Trump?

What did Starmer actually get out of Trump?Today's Big Question US president's remarks, notably on tariffs and the Chagos Islands, were encouraging but vague

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK